Christians in the western part of Guinea say they are being harassed by predominantly Muslim Indonesia

Despite the success of evangelism efforts in West Papua, the western part of the Island of Guinea, Christians there say they are struggling to survive in a climate of religious and political oppression.

Despite the success of evangelism efforts in West Papua, the western part of the Island of Guinea, Christians there say they are struggling to survive in a climate of religious and political oppression.

Although they comprise a majority of the region’s 2.5 million people, Christians in West Papua say they are being persecuted by predominantly Muslim Indonesia, which took over in 1963.

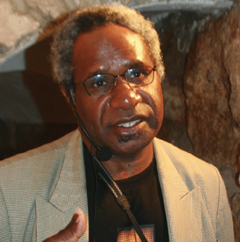

“The missionaries should have prepared us for this,” said pastor Lipiyus Biniluk, president of the Evangelical Church in Indonesia, a network with 900,000 members. “They told to us to go to Bible school, but did not encourage us to get any vocational training.

“In consequence we are now completely in the hands of the Muslims. They control everything—our banks, our shopping malls, our hospitals. As Christians we are even afraid to go to the hospital when sick.”

Their fear is grounded in the fact that the Indonesian military killed thousands of civilians after West Papua was formally annexed to Indonesia in 1969.

Formerly a Dutch colony, West Papua was in the 1950s on the verge of becoming a sovereign state, like the other half of the island, known as Papua New Guinea. But it became embroiled in Cold War politics. Under intense international pressure, the Dutch agreed to transfer sovereignty to Indonesia in a deal brokered by the U.S.

The agreement stipulated that West Papuans would vote in a United Nations referendum to determine whether they wanted to remain with Indonesia or become an independent state. But rather than allowing each adult to vote, Indonesian officials chose 1,022 representatives, who voted unanimously to join Indonesia. Many observers still question the legitimacy of the referendum, saying the votes were obtained under duress.

West Papua is still home to some of the world’s most underdeveloped communities. German missionaries began reaching out to the cannibal tribes living in the coastal jungles in the mid-1800s. But as recently as World War II the outside world did not suspect the presence of humans in the inaccessible highlands, where Biniluk’s church was founded.

Wupu Game, a church leader from the Dani tribe now in his 60s, still remembers the day when missionaries first arrived in his community in 1955. “They came with salt,” Wupu recalls of his first contact with the outside world. As the son of an elder, Wupu got to taste this extreme rarity. He also watched as one of the missionaries was killed with a poisoned arrow.

But before long, Game’s parents and their whole tribe embraced the gospel. “What intrigued us was that Jesus had risen from the dead,” Game said. “My tribe used to live in a constant fear of death.

“Older people would hear a certain bird cry during the night and inevitably somebody died on the next day. We were traumatized. Mothers would cut off a finger for every child that died. And the medicine man tried all kind of witchcraft to make the dead come alive again.”

When the tribe decided to put their hope in Jesus, all amulets and other witchcraft devices were burned in big bonfires. Game recalled the relief they felt and how things became so very easy. Tasks that used to keep people busy for months took “no time at all” with the new tools the missionaries brought, such as knives, and axes.

Today life is not easy for the West Papuan Christians. Besides harassment by the Muslim regime, church leaders said another crisis is developing. Diseases such as malaria and HIV are spreading, as well as an “unknown epidemic disease that the government does not even bother to investigate,” Biniluk said.

“I am completely worn out by all the funerals I have been holding lately,” he said. “There is no information given about HIV, and our church members have no money to buy malaria medicine.”

In October, Biniluk joined a delegation of indigenous church leaders who flew to Jakarta, the capital, to plead with the Indonesian government to allow West Papua to implement the special autonomy that was formally granted in 2001. “So far it has been words only, in reality nothing has changed,” he explained.

Addressing the issue of autonomy could be dangerous in a country that does not even allow free press. “But we have to try,” Biniluk concluded, “or our people will not survive.”